At the heritage site Skriðuklaustur are the ruins of a 16th century Augustinian monastery. The monastery was founded around 1493 but came to an end during the Reformation in 1550. In the following centuries, the history of the monastery was almost forgotten, but was revealed in an archaeological research project in the years 2000-2012.

The beginning

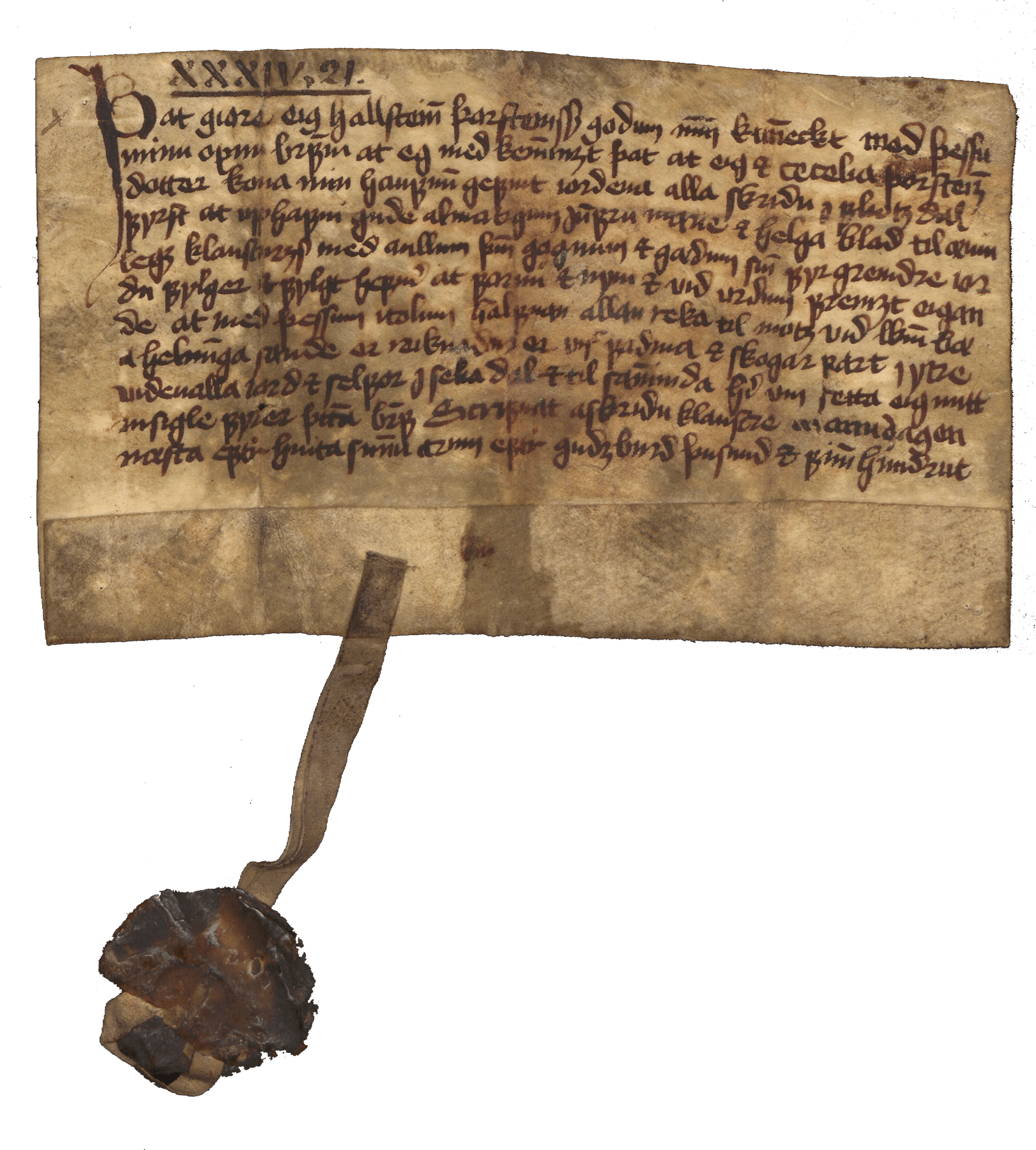

Skriðuklaustur was the last cloister to be founded during Iceland's Catholic period, which ended with the country's 16th-century Reformation. It was thus active for less than six decades and could scarcely be said to have flourished for more than about four decades. The deed of gift is still preserved whereby the couple Sesselja Þorsteinsdóttir and the local sheriff Hallsteinn Þorsteinsson, who lived on the other side of this valley at Víðivellir ytri, donated Skriða farm as the site for a cloister. Although this deed was signed on 8 June 1500, it is believed that the cloister was founded sooner, probably in 1493 when Stefán Jónsson, bishop at Skálholt, came on his first visit to the valley.

The end

Skriðuklaustur had only been in operation for a short time when events began on the Continent that eventually resulted in the Reformation. Following this, the King of Denmark took over all the cloisters and their property in Iceland, as the country was under the Danish crown at this time. However, Skriðuklaustur was allowed to operate under an exemption for over a decade. Formal operations finally ceased when the king leased the cloister and all its assets to a Lutheran pastor farther down the valley. The document to this effect was signed on 12 September 1554.

Everything indicates that the monastery buildings were simply allowed to fall into ruin after usable objects and wood had been removed. The church continued to stand, though, and was placed under the responsibility of the king's Skriðuklaustur agent. Gradually the church became dilapidated, but a smaller one was erected over its ruins around 1670. The latter church was finally deconsecrated in 1792, although the cemetery had already fallen into disuse much sooner.

Ten-year digs

In the summer of 2000, a preliminary site investigation located the ruins in a field next to an old cemetery. Excavation started in 2002 until 2012 when the site was officially opened for visitors.

Archaeologist Steinunn Kristjánsdóttir led the study of the monastic ruins and, on average, fourteen archaeologists excavated each summer for 8-9 weeks. Experts in other fields worked on the project as well. All together, 131 individuals from twelve countries worked on the research at the Skriðuklaustur monastery, during preparation, the excavation itself and specific analysis.

To start with, research focused on excavating the remains of the church and other buildings, and finding out about the monks’ daily lives. Special efforts were made to find evidence of their literary work, in keeping with accepted ideas on Icelandic cloisters. However, the focus of the study soon switched to the cloister cemetery, which turned out to be an important source of information on daily medieval life, the health of commoners and the facilities for charity and nursing.

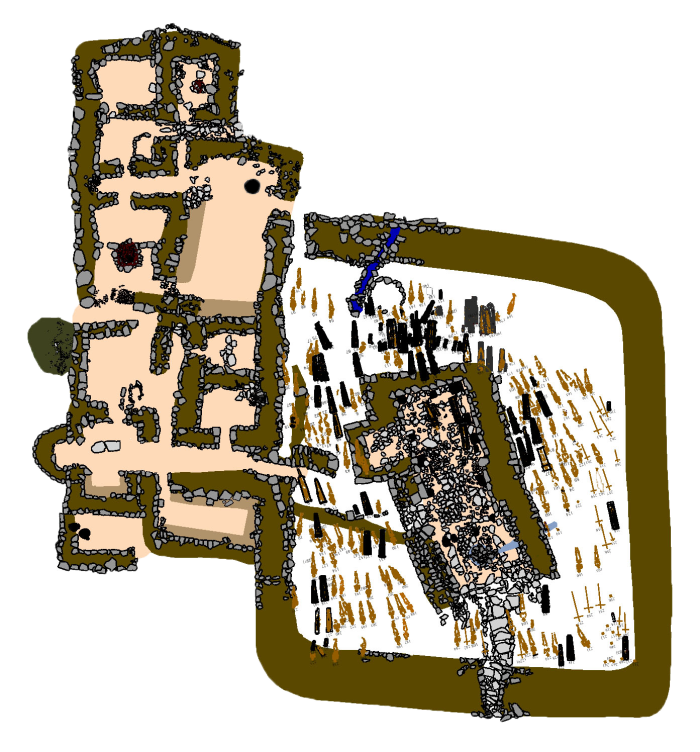

The Buildings

In total, the buildings here covered around 700 square meters (7500 sq.ft.) – in part built on two floors. The church was the largest and connected the main cloister with a hallway. In addition to a church and cemetery bounded by a stone wall, there were a variety of cloister rooms which differed in size and type: a sleeping section, a kitchen section with a separate dining area, and a section with work and storage facilities.

Ever since the excavation ended at Skriðuklaustur in 2012, all the findings from the dig have been researched, catalogued and shared through different media. In 2012 the first 3D model of the buildings was made, which became the foundation of a detailed 3D model made by the University of St. Andrews through the CINE project. That model has since been updated using Unreal Engine and now it is possible to walk around the cloister buildings using an Oculus VR headset. A preview of virtual reality is shown in the video.

Church

Infirmary (upper floor)

guesthouse (first floor)

Night stairs

Kitchen

Cemetery

Brewery

Pantry

Warming house

Dormitory

Chapter house

Cemetery

Cemetery

Cemetery

Refectory

Ambulatory

Working space

Storage

Outer kitchen

Rubbish heap

Well

Entrance

Church gate

Cloister-gate

Paved corridor

Most of the Skriðuklaustur buildings appear to have been erected during a continuous construction phase in the 1490s, although the church was built later and consecrated in 1512. The oldest building might be the lodging quarters by the cloister gate. Since the founders of medieval cloisters emphasised charity and care, they often put up the lodging quarters first. Forming a sort of core around which other operations revolved, such quarters represented a shelter for travellers and pilgrims, in addition to being a haven for the sick and poor seeking mercy at such cloisters. Later buildings were then added around these lodgings.

There are no written descriptions of the monastery buildings, but in audits after the monastery period, several items are mentioned in connection with the church giving permission for the building and its infrastructure. Those documents also list other buildings and extensive farming work right where the house of Gunnar Gunnarsson is standing now.

Building materials

The cloister walls involved large-sized dry stones, i.e., no cement was used, though some of the rocks may have been shaped to an extent. There were plenty of usable stones in the cliffs, either just below the site or a short way up the slope. Each wall was made by piling two parallel rows of rocks that determined the wall's thickness, then digging soil to deepen the room being built between walls, and filling and compacting this soil between the piled rows of rocks. Strips of turf were sometimes laid between the two rock rows in the wall in order to tie them together. When such a wall had been piled high enough, a support structure could be placed on it for the roof, which in the end was covered with turf. None of the support structure was found during excavation, since all of the wood was used for construction elsewhere when the cloister fell into ruin. Originally, such wood had mostly consisted of driftwood from the coast or local birch, which was used for rafters and the lattice supporting the turf roof. Most of the living quarters had wood cladding on the inside, which in recent centuries was not very common in Iceland, and some rooms even had wooden flooring, though the floors usually consisted of smooth rocks or just packed earth.

Hospital

The study of Skriðuklaustur revealed that the monastery, like other Augustinian monasteries, had been a refuge for the sick and poor. Written sources testify to schooling for children in the monastery, but the history of the hospital was lost until revealed again in the cemetery.

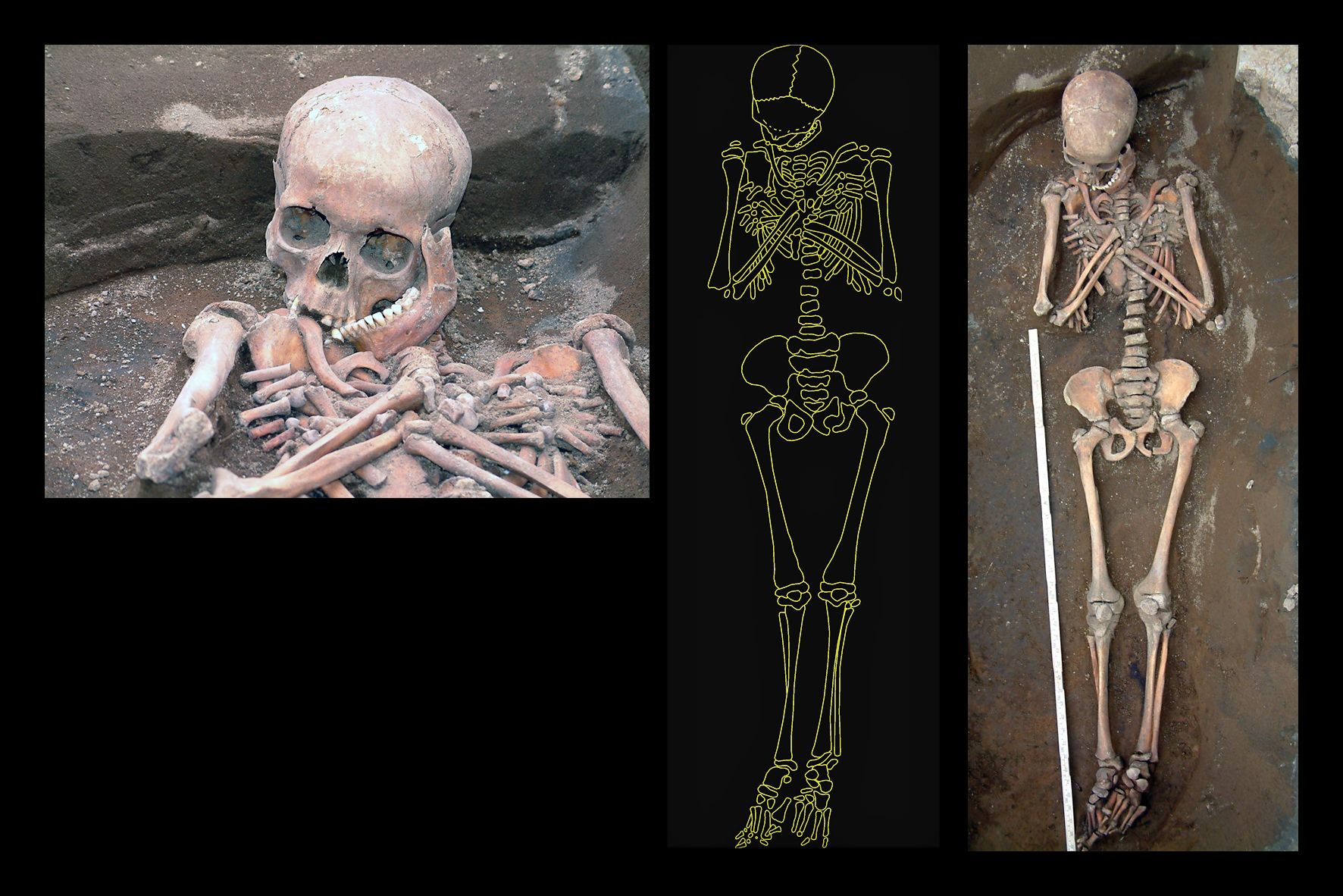

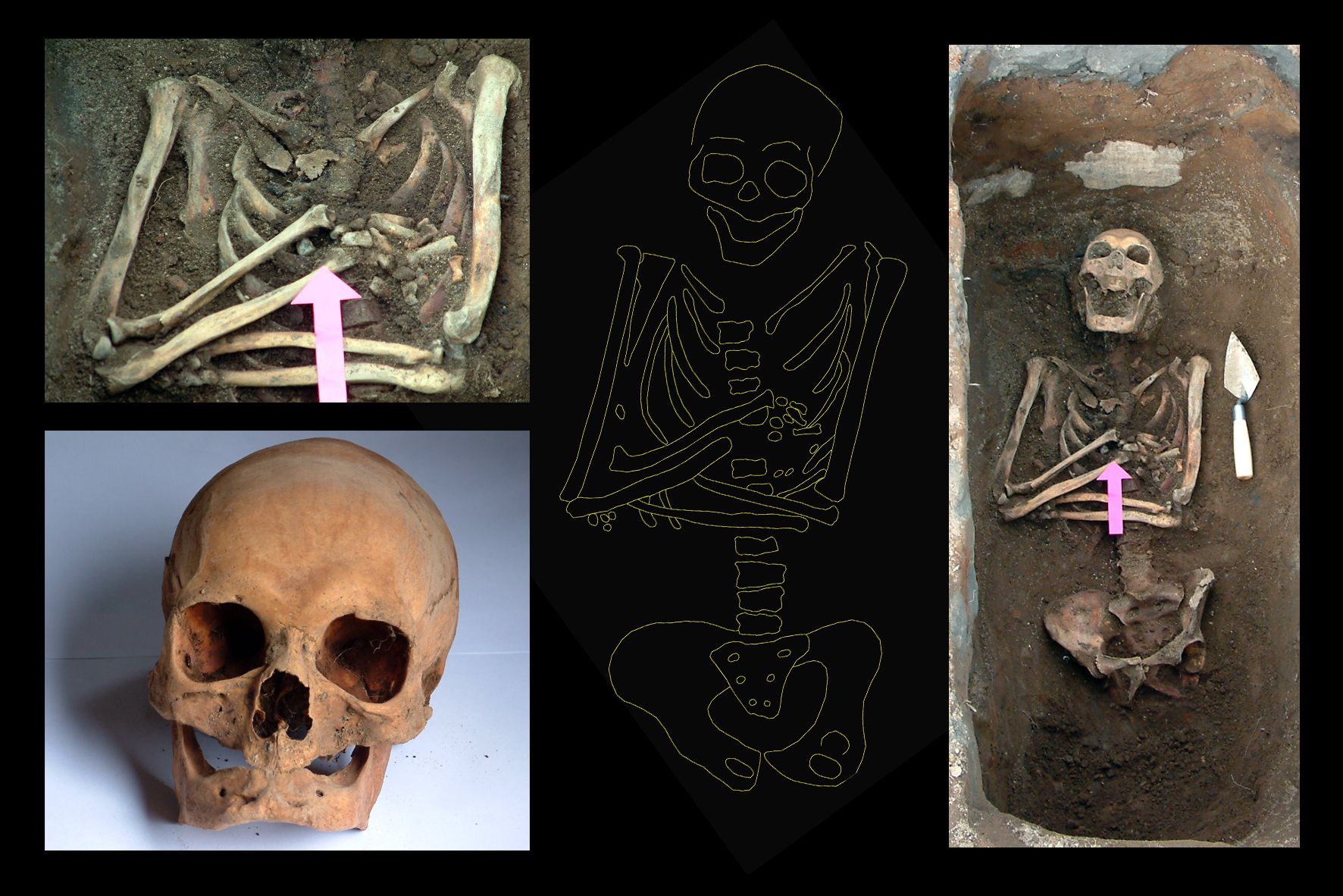

The bones of those who were laid to rest in the cloister cemetery display the suffering of those who sought help from the monks here. Many patients had been disabled since birth, through sickness or accident; others suffered from syphilis, tapeworms or other long-term infections; some stood out in public and were incapable of making a living on their own; still others had difficulty giving birth or were considered undesirables. The cloister was open to everyone, with the monks providing a consecrated resting place even to the unbaptised stillborn. Additionaly, the bones show clues that numerous people besides the monks worked here to help others lead a better life.

Cemetery

Bones from a total of almost 300 individuals were found in the cemetery, which is estimated to be about 1% of the Icelandic population in the first half of the 16th century. 242 graves were excavated. Half of them were the bones of patients, about 130 were considered to be the bones of unconsecrated individuals and 20 were consecrated.

The collection of human bones from Skriðuklaustur is the largest in Iceland from a single excavation. It counts 260 preserved skeletons, whole or in part. Although no one knows the names of these individuals, their bones provide invaluable insight into the society and health of this bygone era.

Artefacts

Over 13,000 artefacts and bones were recorded during the archaeological excavation. Conditions at the site were good, which meant that everything down to the smallest fish bones had been preserved in the soil. Not many complete items were found, as everything useful was removed from the houses when they were no longer used. An example of the larger treasures is the statue of Saint Barbara, which was found in many fragments in the ruins of the church. One fragment of the statue, the face itself, was then found in the kitchen two summers later during the excavation.

Part of the CINE project was to create three-dimensional images of selected objects. This photogrammetry technology allows the user to carefully view the artefacts on the screen and is useful for both dissemination circulation and further research.

Heritage site

The excavation area covered about 1500 square meters (16,000 sq.ft.). The ruins were not deep under the surface and the average depth of the excavation was about one meter. During the ten years that the excavation took place, the archaeologists moved about 200 truckloads of soil and rocks.

Most of the material was placed back in the area when finished. Low walls were built of stone, earth, and turf to show the basic structure and layout of the buildings. Graves and uneven surfaces were filled with soil and larch pellets were placed in the spaces that were considered indoors. This way, the ruins were made accessible to the public and information signs were placed in each room. A viewing platform was also built on a cliff above the ruins.

With the help of technology and 360° images, images from the area and from the virtual world of the CINE project have been placed on the Roundme portal, making it possible to visit the site online.

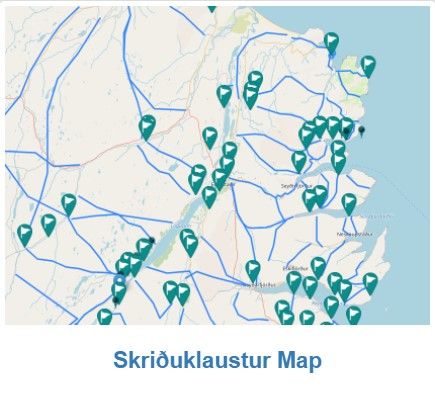

Land holdings and travel routes

The upkeep of Icelandic medieval cloisters was mainly financed by managing farms and by receiving gifts for people's souls, accepted in the form of food or clothing. During its short history, Skriðuklaustur was associated with 60 farms. Most of the farms were in East Iceland, and many included tenant farms. Farm estates were Skriðuklaustur's leading assets and source of wealth. Rents were usually paid in goods, for instance as homespun woollen cloth, butter or other foods, livestock, dried fish, meal, driftwood, charcoal or even kindling wood.

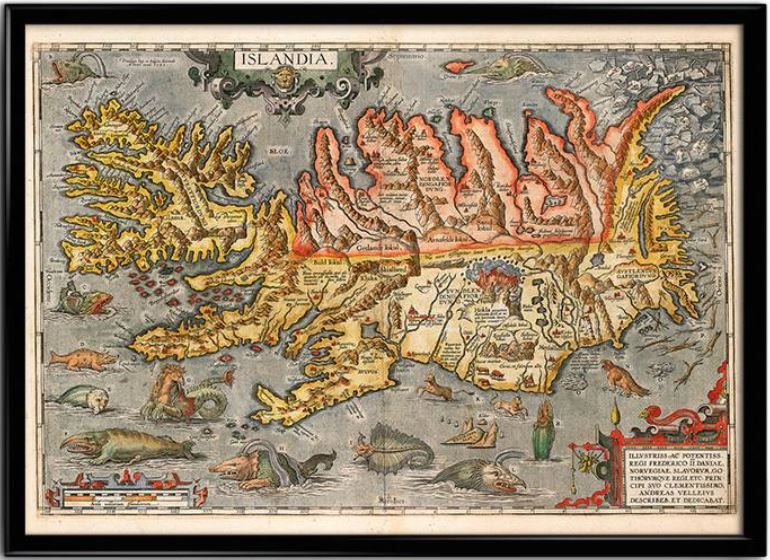

The monastery farm Skriðuklaustur is large, over 10,000 hectares (100 sq.km), with extensive grassy pastures. It stands by an ancient national route where the main route to North Iceland has for centuries been on Fljótsdalsheiði (the heath above Skriðuklaustur), where there is now a paved road up the gorge of the river Bessastaðaá. Lagarfljót was a barrier to travel, which forced riders who were going east to use the crossing over Jökulsá in Fljótsdalur on their way to the Eastfjords. During the time of the monastery, the main trading place of East Iceland was in Gautavík in Berufjörður, and there was a route through Suðurdalur in Fljótsdalur valley. The route to the fishing station in Suðursveit was Norðurdalur in Fljótsdalur valley and then south over, what was then a much smaller Vatnajökull glacier where now is Brúarjökull.

Skriðuklaustur stood at a crossroads like many other medieval monasteries and provided travellers food and shelter.

→ The map opens in another window. There you can choose what appears at any given time.

You need to select what you want in the "layer" and then ⟳ to see each layer individually.

By clicking on the map, you can view the farms and travel routes related to Skriðuklaustur during the monastery period.

Routes and boundaries are roughly drawn on the map for graphical representation.

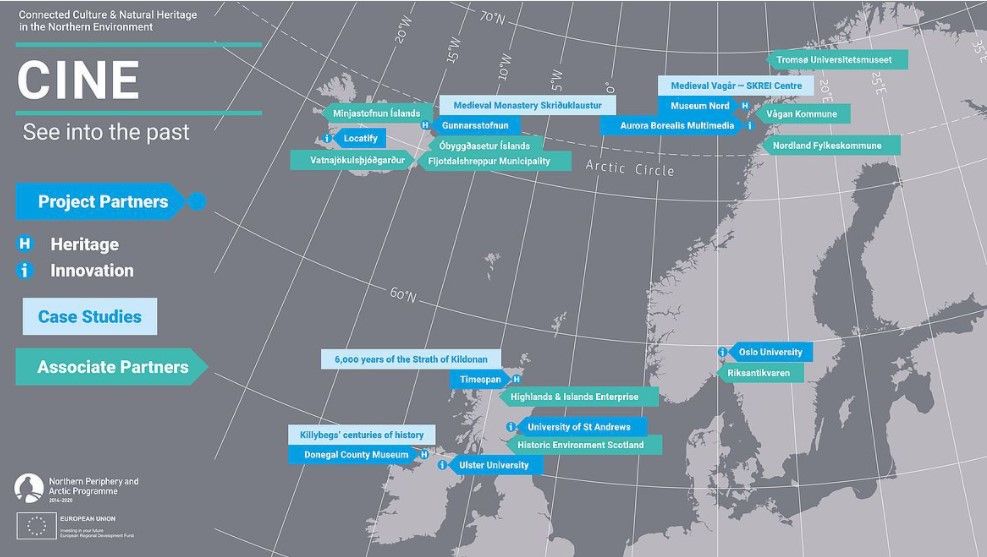

The CINE project, Connected Culture and Natural Heritage in a Northern Environment, aims to transform people’s experiences of outdoor heritage sites through technology, building on the idea of “museums without walls.” New digital interfaces such as augmented reality, virtual world technology, and easy-to-use apps will bring the past alive, it will allow us to visualise the effects of the changing environment on heritage sites and help us to imagine possible futures. The CINE project was supported by the EU Arctic Program. It began in the autumn of 2017 and lasted until the end of 2020. Partners in the project were museums, cultural centers, institutions, universities and other parties in Norway, Scotland, Iceland, Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Skriðuklaustur case study

The Gunnar Gunnarsson Institute worked on the project with the development of dissemination and data collection of the medieval monastery. Various technologies were tested with the aim of developing a toolbox that enables museums and scholars, individuals and communities, to create an innovative approach to natural and cultural heritage and experience on site or at home in the living room. Part of the result can be seen above.

Route over Vatnajökul glacier

The route that workers from Skriðuklaustur went to a fishing site in Hálsahöfn in Suðursveit 500 years ago was researched specifically. This route was partly over Vatnajökull, which was many times smaller in the 16th century than it is today. Collaboration was carried out with the Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, the National Land Survey of Iceland and other scholars to shed light on the path that had been taken and the changes that have taken place in vegetation and glaciers since the monastic period. Footage was collected on the spot and shared through virtual reality and a touch screen to show this ancient journey. One can wonder when the glacier route will be passable again due to climate change.

Gamifaction and cultural communication

The utilization of games and gamification in cultural communication was one of the issues addressed in the work package for which Icelanders and Irish were responsible. A large seminar and Think tank was held under the title “Let's play with heritage” and experiments were made with a game and location system from the Icelandic company Locatify, which is also a member of CINE. A practical handbook was written on gamification and game-based approach to cultural heritage. It was also examined how best to work on the preservation and dissemination of cultural monuments with the local community. Guides and other results of the work package can be found on cinecommunities.org and cinegamification.com.

Project partners

Associated partners of Gunnarsstofnun and Locatify in the CINE project were: The Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland (Minjastofnun Íslands), Vatnajökull National Park (Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður), Fljotsdalur Municipality (Fljótsdalshreppur) and The Wilderness Center (Óbyggðasetur Íslands). In addition, input from many others and various side-projects have become a reality with grants from the East Iceland Development Fund, Friends of Vatnajökull, the Fljótsdalur Community Fund and the Student Innovation Fund.